Consider the following prediction by Matt Ridley, in his 2010 book The Rational Optimist:

I forecast that the twenty-first century will show a continuing expansion of catallaxy — Hayek’s word for spontaneous order created by exchange and specialisation. Intelligence will become more and more collective; innovation and order will become more and more bottom-up; work will become more and more specialised, leisure more and more diversified.

Catallaxy is an alternative to the term economy, emphasising the emergent properties of exchange not among actors with common goals and values, but rather among actors with diverse and disparate goals, a concept central to the Austrian School of which Friedrich Hayek was a renowned contributor.

Could one argue that Ridley’s prediction, and Hayek’s definition of catallaxy, represent a central tenet of Industry 4.0? In other words,

should we be discussing Industry 4.0 catallactics rather than economics?

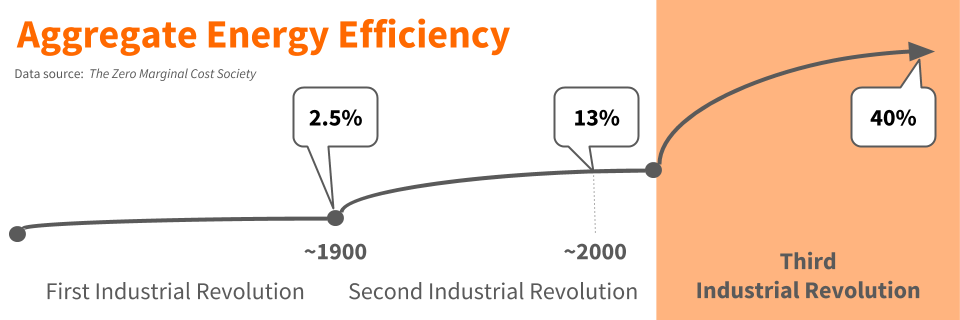

While those questions are far too broad to address in a blog post, we can nonetheless address a single concept that we at reelyActive believe to be core to Industry 4.0: ubiquitous real-time location. If computers are able to understand who/what is where/how in any physical space, they can elevate efficiencies by magnitudes rivalled only by previous industrial revolutions. For instance, Jeremy Rifkin argues for a trebling of aggregate energy efficiency from 13% to 40% or more.

But alas, applying ubiquitous real-time location to the benefit of “actors with common goals and values” too easily equates with Big Brother, or surveillance by a state or entity, typically under the auspices of the “greater good”. In short, top-down organisation of ubiquitous real-time location is likely to restrict the free exchange of real-time location data, and hence the efficiencies of Industry 4.0, unless all actors’ interests are aligned.

And it is not difficult to argue that the actors—individuals, entities and their assets—are not aligned and do indeed have “diverse and disparate goals”. For instance, when you walk into a store, you may be motivated to find what you’re looking for as quickly as possible while a salesperson may be motivated to upsell you, while a competitor may be motivated to promote their product or get you into their store. If a delightful retail experience is to spontaneously emerge, it will be the result of the voluntary exchange of location data by the “motivations and actions of individuals”: the basis of the Austrian School. In short, bottom-up organisation of ubiquitous real-time location arguably affords better outcomes to actors with competing motivations, especially when those actors and their interests vary so greatly across countless industries and contexts!

Would it be possible to imagine an emergent Pervasive Sharing Economy as anything but bottom-up?

Perhaps the closest thing to ubiquitous location we have today is through mobile, hence the retail example above. In Still Place for optimism? we illustrated how industry relies on top-down “baseline location data” where, often to the detriment of the located mobile user, that user’s competing interests are ignored rather than embraced. Couple this with state surveillance by means of mobile location data, and it becomes very difficult to make the case for a top-down approach as the catalyst for the widespread exchange of real-time location data necessary to deliver the promised efficiencies of Industry 4.0.

So, returning to Ridley’s prediction, the case for expansion of the catallaxy and bottom-up order is therefore strong, provided we can break from the long-standing top-down traditions of Industry 3.0. But isn’t breaking established traditions what revolutions are all about? And if we are to break from tradition, the economy of Industry 4.0 may well be described as a catallaxy. At least in the case of ubiquitous real-time location it’s difficult to imagine otherwise!